5.1 - Our Brains Aren't Adapted to Process Our Present Situation

For most of the time that life has existed on Earth, big changes happened too slowly to be perceived. A human born during an Ice Age could expect things to stay Ice Age-y for their whole lifetime. A human born in a rainforest could expect it to remain a rainforest, for as long as they were around to witness it.

Meanwhile, the main threats and the requirements to survive them selected for humans who:

Assumed that general conditions will stay more-or-less the same - The “background” stayed the same, so we could ignore it without consequences, and channel our energy to the action in the “foreground”.

Made simple, snap judgments - If you think you see a poisonous snake, it’s safer to assume so and react, than to spend time debating or scrutinize it up-close, even if it might just be a stick.

Sought acceptance like their life depended on it - For humans, survival as always been a team effort. Ostracism was akin to a death sentence, so you did your best to earn the group’s embrace.

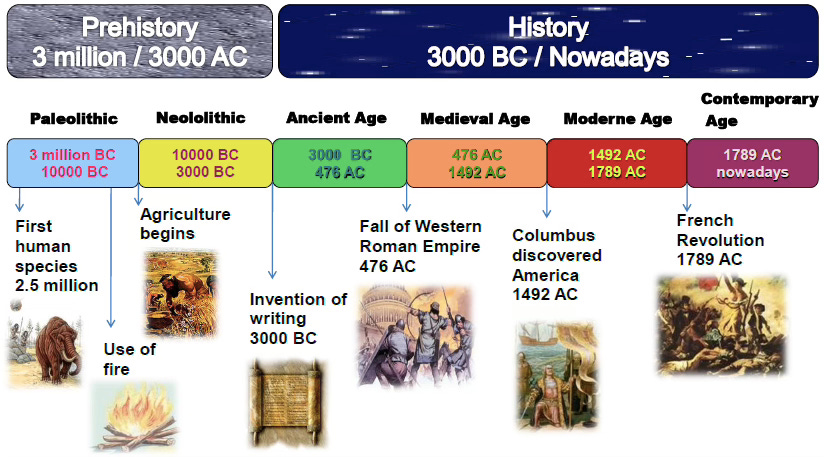

If the above timeline were to-scale, we’d see that civilization-esque interactions and their unfathomably big impact are extremely recent. The repercussions that human civilizations have triggered on a regional basis over the past 12,000 years and the consequences that we’re experiencing now that we’ve “taken our approach global” are totally distinct from the situations that shaped our brains during the 2,500,000 million years that preceded. Our minds can’t handle the signals properly. We therefore reject the information, or even when we accept and process it, it feels unreal.

“Classic” Biases & Today’s Awkward Applications

Black-and-White Thinking - We can’t spend time contemplating the nuances of every situation, so we make snap judgements based on available information and proceed in problem-solving mode. Sometimes, this looks like a tendency to identify an enemy so that we can take action against them. This framework isn’t well-suited to situations where the relationships among elements are more complicated, where to eliminate an undesired impact would require eliminating a desired element.

Loss Aversion - The pain of losing $100 is worse than the thrill of winning $100. (In the past, those who didn’t feel loss strongly would’ve taken too many risks and “gambled away everything".) When we consider making significant life changes to brace for civilization’s decline, we perceive what we’d sacrifice (e.g. foregone income and retirement savings -ha!-, others judging you as a failure or a whacko) more strongly than what we’d gain (e.g. reduced future suffering).

Hyperbolic Discounting - We perceive present impacts more strongly than future impacts. People will prioritize relief-from-distress in the present, even if that means compromised wellbeing in the future. For example, someone might learn that, as supply chains deteriorate, their location will not be able to sustain its human population. Even if they have the means to relocate, their current state of fear (or anxiety at the thought of transferring to a lower-status job in a safer region) will feel most prominent (stronger than the bad emotions that they can anticipate feeling in the dangerous area in the future), so they will prioritize relief and suppress the thought. Ironically, as a result of suppressing the earlier emotion, they will face worse states in the future, in the form of real hardships.

Sunk Cost Fallacy - A person will overvalue existing investments and stick with them even when it would be wiser to abandon them. For example, if someone resides a house in Florida that they had to work hard to afford, they might cling to it even when the data indicate that to protect their wellbeing, they should abandon their dream home.

Dunning-Kruger Effect - A lack of knowledge and skill in a certain area causes people to overestimate their own competence. For example, those who are outspoken about climate often have less awareness of or fail to incorporate the multiple facets of our predicament.

2-minute video of John Michael Greer on our state of denial:

Normalcy Bias - We cannot fathom ideas that are too outrageous. Most people alive today have grown up in a world with farms and cities and governments and schools. If any disrupts them, we assume they’ll bounce back. (When in 1977, two airplanes collided on a runway, some people escaped, but others sat frozen in their seats -unable to act because the situation was too wild to process- and died in the flames.)

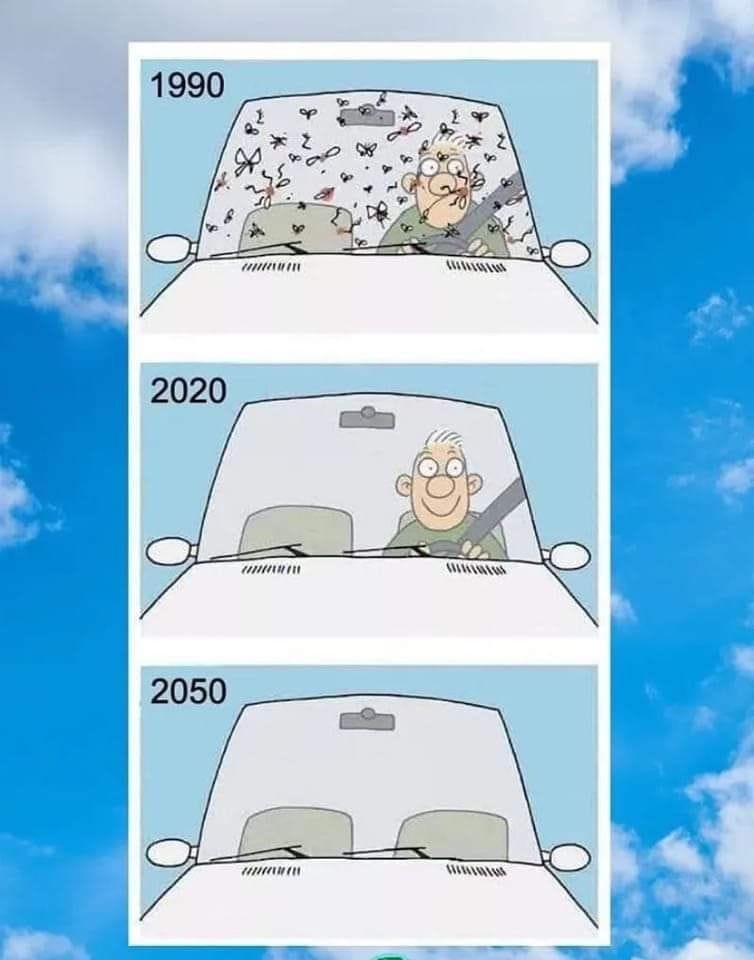

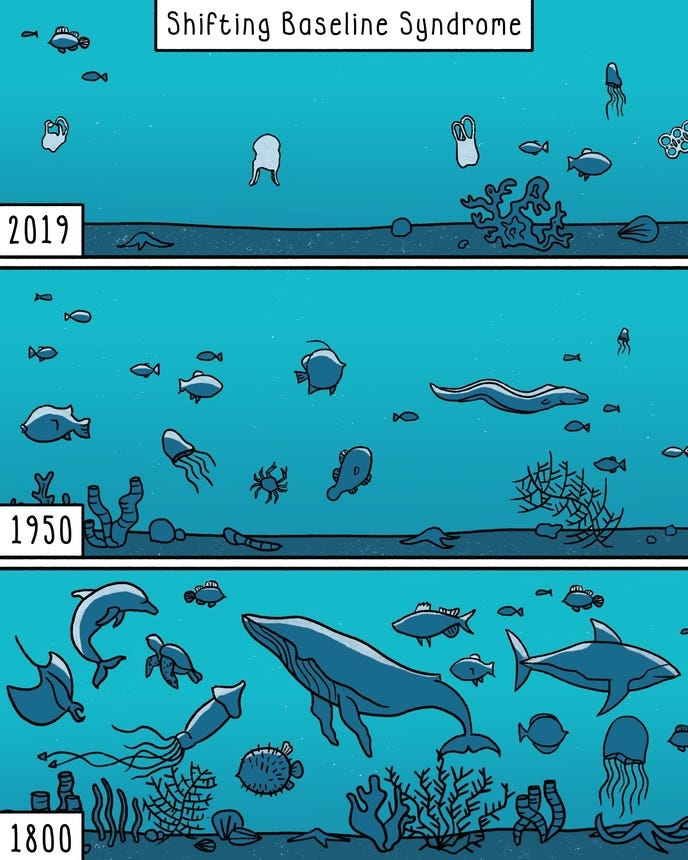

Receding Goalpost / Shifting Baseline - Things steadily, imperceptibly get worse and we acclimate to them. If your 2000 self saw headlines from the 2020s, you’d be shocked, but because it’s a gradually-increasing background hum, we don’t notice it. Below are some cartoons that illustrate this.

Informational Social Influence - As social animals, we look to each other for signs of how to respond. No one else is panicking, so we assume that there is no reason to panic. But the reason we don’t see more people panicking is because they’re all looking around at each other, too. (A 1968 study pumped smoke under a door into the room of participants and they hesitated to react.) (Interestingly, intelligence does not have a significant relationship to conformity-susceptibility, but “openness” helps.)

Furthermore, for our indigenous ancestors, to be ostracized meant death. Members of a civilization don’t need to worry about this as much, since they acquire food by performing tasks for an employer in exchange for money, which they exchange for food. Social status isn’t as tightly correlated with staying fed. Nevertheless, we’ve retained our aversion to displeasing others, and so we avoid saying things that will dismay.

Mortality Salience & Worldview Defense - According to Terror Management Theory, we look to culture to protect us from having to grapple with the thought of our own inevitable deaths. Imagining that your religion or favorite sport/cuisine/painting will exist long after your death brings a sense that you will live on with it. When we hear that those too will be annihilated, we feel even more deeply threatened and resist. This relates to two other concepts:

“sustained incoherence” (David Bohm) - In response to evidence that is not compatible with our convictions, we display “a reflex defensiveness in thought that leads instead to obstinate continuation”, rather than reassessing and reorienting. Similarly, John Gray defines the theory of cognitive dissonance and how humans resolve it: “Human beings do not deal with conflicting beliefs and perceptions by testing them against facts. They reduce the conflict by reinterpreting facts that challenge the beliefs to which they are most attached."

“wetiko” (a Native American concept which Paul Levy describes) -

“People under the sway of wetiko are implicated in and willingly subscribe to their own enslavement. They do this to the point that when offered the way out of the comfort of their prison they oftentimes react violently. They symbolically—and sometimes literally—try to kill the messenger who is showing them the path to freedom.”

Confirmation Bias - People tend to seek information that justifies what they already believe (and which they want to be true). Anyone who feels dread and seeks only reassurance about civilization’s prospects will find plenty of reassurance. They’ll be disinclined to question the ideas’ truthfulness and the actions’ efficacy, because this might reveal the notions’ flimsiness.

We Take for Granted What Operates in the Background

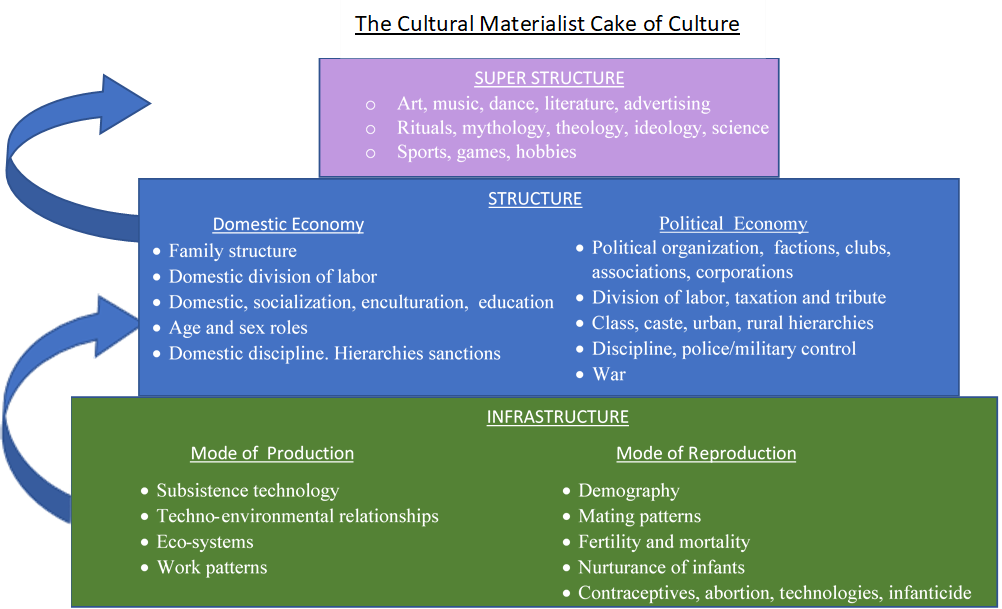

The “cultural materialism” theory suggests that infrastructure (material conditions, modes of meeting basic needs, relationships with nature and technology) dictates a society’s structure (norms, rules) and its superstructure (ideology). High-energy modernity emerged, and then our ideology formed to reflect and justify it.

Our infrastructure shapes our thinking because it’s the layer that we take for granted. It operates in the background. In a society where the refrigerators run, tap water flows, trucks deliver food and toilets flush, we forget to factor the complex systems that support them into our visions. We are incapable of picturing an existence too similar to other species' Normal, or a fate as grim as the one that our repeated experiments in “civilization” have inflicted on other life.

As long as civilization’s extraction-oriented model persists, we’ll be unable to think outside of it. That’s why, even as heat damages London’s airport runways and makes Formula 1 drivers vomit in their helmets in Qatar, we find ways to keep flying and racing. The show must go on. Our habits, norms and codified rules will continue to impede an appropriate response.

Only as civilization deteriorates, such that people have to meet basic needs independently of its systems and physical infrastructure, will they truly be able to think and act differently.

Other Research and Observations

Iain McGilchrist, author of “The Master and His Emissary”, makes a valid observation about our contemporary mode of thinking (regardless of whether brain function is actually divided between the left and right sides):

We “pay narrow-beam attention focused on the detail that we already know and desire and are intent on grabbing … simplified in the service of manipulation ... devoid of context, disembodied.”

Such logic will be “unreasonably optimistic and fails to see the dangers that loom.”

“The metacrisis is the predictable outcome of a complete failure to understand what a human being is, what the world is and what the one has to do with the other.”

"When reality refuses to be selected, cropped, and edited out, we are left unequipped to deal with it." - Vanessa Machado de Oliveria, “Hospicing Modernity”

Rebecca Weston, psychotherapist and co-president of the Climate Psychology Alliance of North America, notes:

“I don’t think people like facing things they can’t affect … And in trauma, people do everything that they possibly can to stop feeling what is unbearable to feel.”

“We can be told something over and over and over again, but if we have an identity and a sense of ourselves tied up in something else, we will almost always refer to that, even if it’s at the cost of pretending that something that is true is not true.”

One study found that if something challenges how we already define our self-esteem, self-efficacy and in-group/out-group, we resist it.

And as the Upton Sinclair quote goes, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

The “Breaking Down: Collapse” episode on “Psychological Barriers to Confronting Collapse”

Bill Rees presentation on “The Enigma of Climate Inaction – On the Human Nature of Policy Failure”

From Nate Hagens’ roundtable with Tom Murphy and DJ White:

“Most people think in sentences that are told to them by other people”

“The one word that I think characterizes our big blind spot is ‘context’. So many problems are defined narrowly and thought of narrowly so that you're missing the great majority of the reality. The demographic transition worked for European and Western countries because the context was an exploitable world that was not yet denuded.”

"You can't expect a university to understand something that its funding depends on it not understanding"

May I be so bold as to add Umwelt and hyperobjects to the list?

We perceive the world through senses that filter out what is not needed for us to live and reproduce. We can expand this with tools and reason but it still must be translated into what our senses evolved for, so we cannot see it "as it is", only via "screens", be that a monitor, an equation, etc.

Hyperobjects are entities composed of nany other interacting entities with volition of their own, like civilisations, money, weather, etc.

The two, unwelt and hyperobjects, are irreconcilable. We cannot ever understand enough to make any sort of action that will be as we want without unforeseeable consequences.

These are all salient, important points, but a better mental capacity for the truth about the human predicament wouldn't solve an unsolvabke thing.

If global.civilzation.is a heat engine, as Tim Garrett has proven, how could a global degrowth soft machine even be envisioned? All fossil fuel.machines, across the world, instantly disabled?.With what violent force - look at the anti-green backlash already in Alberta to see how that would go